Featured in the San Francisco Public Press:

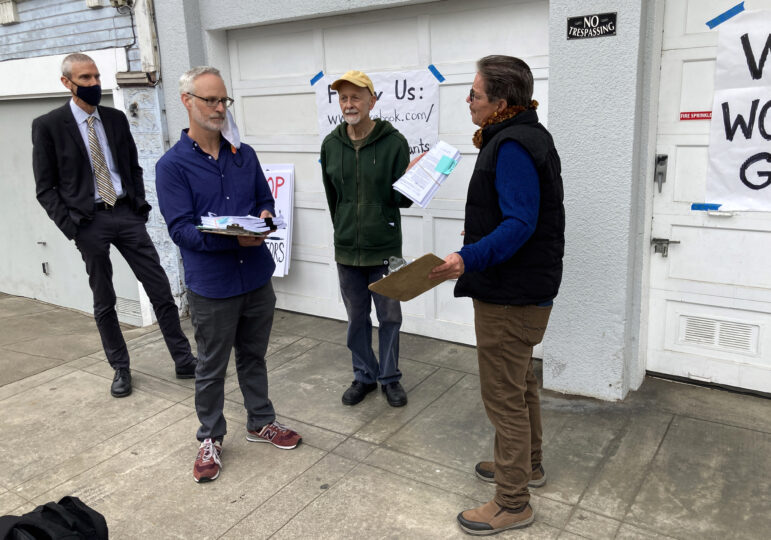

Credit: Noah Arroyo/San Francisco Public Press

The Veritas Tenants Association has been

trying for more than a year to get Veritas, often called San Francisco’s

largest landlord, to negotiate a rent-relief package for tenants who

faced COVID-19 financial hardships. Debbie Nunez, left, and other

association members assembled outside the company’s headquarters in

October to draw attention to the impasse, which pending local

legislation could resolve.

Renters throughout San Francisco could gain power to lessen COVID-19

financial hardships and improve conditions in their buildings with

political-organizing tools that have a history of success in subsidized

housing.

In coming weeks, city supervisors will weigh legislation that would

make it easier for tenants to form associations, similar to labor

unions, that could compel landlords to hear them out on a range of

issues, including the aesthetics of new construction and other matters

affecting the bottom line for owners.

The proposal, authored by Supervisor Aaron Peskin, is inspired by

protections that tenants in federally assisted housing secured 20 years

ago — and might be the first legislation in the nation requiring private

landlords to sit down and bargain.

The San Francisco Apartment Association, a property-owners group with thousands of members, opposes the legislation.

This is “all about power,” said Brad Hirn, a tenant organizer with

the Housing Rights Committee of San Francisco, one of about a dozen

tenant and labor groups that collaborated with Peskin and his staff as

they crafted the legislation. “Power comes from organized people. And

the legislation creates a tangible reason to organize,” Hirn said.

A lone tenant may have limited ability to persuade a bad or

neglectful landlord to take requests seriously, and might back down in

response to scare tactics like eviction threats. A group of tenants

could be harder to frighten or ignore.

A response to landlords who stymie organizing efforts

Peskin’s legislation

would explicitly protect San Francisco renters’ efforts to form tenant

associations, which would be officially recognized for a building if the

residents of at least half the units signed on. Upon the association’s

request, landlords would have to meet at least once every three months

and confer “in good faith” about tenants’ concerns. The legislation

gives examples of good-faith interactions, such as “responding to

reasonable requests for information” and “negotiating and putting

agreements into writing.”

The requirement to meet and confer is “groundbreaking,” said Fred Sherburn-Zimmer, executive director of the Housing Rights Committee. “We have asked tenant groups around the country. If there is a law that requires this, we have never heard of it.”

If the law were in place and landlords did not follow the rules

requiring meetings, the city’s Rent Board could penalize them by forcing

a drop in rents. Landlords would not be punished for refusing an

association’s demands.

The legislation’s real strength would be in enabling and possibly

normalizing tenant organizing, Sherburn-Zimmer said. An organized group

might more effectively employ strategies — such as drawing press

attention, protesting publicly or even withholding rent — to compel a

landlord to make concessions.

Tenants can already politically organize, but sometimes landlords try

to stop them, Sherburn-Zimmer said. She recalled an instance when

long-time San Francisco tenants asked for her help brainstorming a

response to impending rent hikes, which would force some to move out.

“We tried to have a meeting in the lobby, and the landlord sent

someone to disrupt it, then tried to physically throw me out,”

Sherburn-Zimmer said. The group relocated to a cafe, where they settled

on a request.

“They were like, ‘you bought this building, we know you can raise the

rent as much as you want. Can we at least negotiate the amount of time

we get before the rent increase?’” she said, adding that they requested

reimbursements for relocation costs. The mayor’s office interceded, and

in the end, the landlord gave tenants some of what they wanted.

“It was imperfect, but it was a sign that this could be helpful in

all kinds of situations,” Sherburn-Zimmer said, referring to collective

bargaining with government oversight.

Veritas,

generally called San Francisco’s largest landlord, has also tried to

reduce interactions between tenants and the Housing Rights Committee,

Hirn said, which has hurt organizing efforts.

In early 2020, 76 Veritas buildings

were up for sale. Hirn began visiting them, knocking on doors to

educate tenants about their rights and what to expect in the months to

come. The Veritas Tenants Association was knocking too, welcoming

tenants to join and sign a petition stating a desire to bargain with the

company over the terms of the sale. Veritas then sent tenants a memo

asserting that state law

limited visitors to speaking only with the residents who invited them.

The company warned that, in response to violators, it would call the

police “to protect the security of the building and residents.” It made

good on that threat.

But that’s just one interpretation of state law. By another, a

visiting tenant organizer should be able to speak with anyone in the

building, said Brian Brophy, a tenant attorney at the law firm Tobener Ravenscroft LLP.

“Because a court has not interpreted that specific question,” Brophy

said in an email, “and because there are landlords/property management

companies challenging knocking on doors, there is potential legal risk”

to the tenant organizer.

If passed, Peskin’s legislation would clarify that visiting organizers could talk to anyone in the building.

Veritas declined to comment for this story. However, spokesman Ron

Heckmann asserted that the company does not own or act as landlord for

its buildings. Rather, it “manages apartment assets on behalf of owners

and investors,” he said.

The company has not divulged its full portfolio of properties, which are rent-controlled and legally owned by various limited-liability companies and similar entities. Separately, Veritas created the company GreenTree, which manages conditions and tenant concerns in the buildings.

A boon for the Veritas Tenants Association

Peskin’s proposal is in large part a response to the experiences of

the Veritas Tenants Association, which has over 1,200 members who live

in more than 100 Veritas properties in San Francisco, as well as in

buildings in other cities, Hirn said. The association, which was

involved in discussions over crafting the legislation, has tried for

more than a year to get the company to negotiate on multiple demands

that would address tenants’ financial hardships during the pandemic.

In an attempt to draw Veritas to the bargaining table, more than 50

of the association’s member households have committed through November

to withhold their applications to the state to cover their rent debt — a

combined $5.7 million that would go to Veritas — a move that makes them

vulnerable to eviction.

They will soon vote on whether to continue their “debt strike”

through December, Hirn said. Any delay in applying with the state could

reduce their odds of getting rent assistance, as the programs have

already received more requests than currently allocated funds can satisfy.

The association wants to negotiate a rent-relief package with the company for all members who need help.

For tenants who took on debt to cover rent during the pandemic, the

association wants temporary rent reductions to help people pay off their

credit cards, payday loans or debts to family or friends, since

rent-relief programs will not help with this secondary debt, often

called “shadow debt.”

Members also want the company to never apply the rent increases for

2020 and 2021 that it has so far delayed — that includes the annual

increases that the Rent Board allows, to follow regional inflation, and “passthroughs” that reimburse the landlord for construction costs and other expenses.

If Peskin’s legislation passes, it could give Veritas’ tenants, and

those of other landlords, the tools to pull them to the bargaining

table.

“I think it makes sense, it’s reasonable, it’s overdue,” said Debbie

Nunez, a member of the Veritas Tenants Association. “I anticipate some

pushback form Veritas. That’s just part and parcel with what they do.”

Associations could be useful in less contentious settings too, said

Lee Hepner, legislative aide to Peskin and lead staffer on the

tenant-association proposal.

“I’d like to think this is a tool for building community among a group of tenants,” Hepner said.

A tenant association could weigh in on safety considerations, use of

common areas, laundry-room restrictions and, most importantly,

construction schedules. Hepner said his office has repeatedly heard

complaints from constituents that working from home was difficult

because “in the middle of the workday, water and electricity would shut

off without any warning.” Peskin passed emergency legislation early in

the pandemic to prohibit certain utility and water shut-offs.

Associations might also distill the varied concerns of the entire

group into talking points, similar to the way neighborhood organizations

represent residents’ concerns in conversations with Peskin’s office,

Hepner said.

“At the risk of sounding naive or like I’m gaslighting landlords, this could make their jobs easier,” Hepner said.

‘A solution in search of a problem’

Not everyone is excited about the proposal.

Requests like those from the Veritas Tenants Association are best

decided between the landlord and specific tenants, rather than with an

entire building’s occupants, said Charley Goss, government and community

affairs manager for the San Francisco Apartment Association.

That would be especially true if the landlord were helping tenants

with shadow debt, Goss said, which might be owed to institutions or to

personal contacts without documentation.

“It’s hard to sort of verify the need in an objective way. There has

to be a sort of needs demonstration, which by definition is particular

to the circumstances of that one individual,” Goss said. “You’re

basically looking at a set of factors: medical, child-care expenses,

rent rates, even their history as a tenant.”

He was also skeptical that tenants would collectively be able to

agree on their requests of the landlord, especially regarding

construction issues.

“One person wants the wall patched, but the other one wants to work

in peace,” Goss said. If major construction were on the table, then

“maybe the tenant in Unit 1 is having a kid next month, and they’d like

it pushed off for a year if possible.”

But Goss’ main criticism was that the legislation seemed unnecessary.

“We’re having this conversation like all tenants are underserved,

unprotected, low-income and being snubbed by their landlords. If you

take a step back, I don’t think that anyone thinks that’s the case,” he

said. In response to tenant hardships last year, between 21% and 54% of

landlords reported granting rent reductions each month, according to

surveys by the Apartment Association.

The Apartment Association is in contact with Peskin’s office to try

to “improve the legislation and make it more workable and productive,”

Goss said.

Andrew Zacks,

a real estate attorney in San Francisco, called the legislation “a

solution in search of a problem.” In an email, he said it “implicates

the landlord’s 1st amendment rights” to the extent it punishes their

refusal to engage in negotiations.

Real estate attorney Daniel Bornstein

said he’s concerned that landlords will get treated unfairly when

tenants appeal to the Rent Board, which will have to weigh in on new

aspects of the tenant-landlord relationship.

“It’s one thing to make an assessment of whether there was heat in

the building,” Bornstein said. “It’s another to make an assessment of

whether there were good-faith meetings. That’s fraught with a lot of

what might be circumstantial, and not very apparent.”

“What is ‘good faith?’” he said, and questioned whether a landlord

would be violating the law by merely walking out of a conversation that

became unruly.

Peskin has vetted the legislation with the City Attorney’s Office.

And Hepner said Rent Board leadership has assured him that they could

handle this new extended oversight role.

As for the assertion that the legislation is unnecessary, Hepner

said, “I don’t think anybody can say with a straight face that there

aren’t tenants that have been aggrieved and wouldn’t benefit from a seat

at the table when communicating with landlords.”

The Board of Supervisors’ Rules Committee will review the legislation

before the end of the year, Hepner said. Peskin is on the committee,

and one of its two other members, Supervisor Connie Chan, has

co-sponsored the legislation, making its progression to the full board

all but certain.

‘Right to organize’ in public housing paved the way

The legislation is heavily inspired by similar protections created in

2000 for housing that is privately owned and subsidized by the U.S.

Department of Housing and Urban Development, and in which about 1.3

million households live nationwide.

Those rules, collectively called the right to organize, were “a sea change” for tenants, said Michael Kane, executive director of the National Alliance of HUD Tenants, which fought for the protections.

Kane started organizing in the 1970s and encountered many tactics

from landlords who neglected and sometimes preyed upon their tenants.

“Owners demanding sexual favors of women, vulnerable women, in order

to get an apartment. Very common,” Kane recalled. When tenants tried to

politically organize, he said, owners threatened them with eviction, or

offered bribes to a tenant leader to induce them to step down and

destabilize their group. He said they also sent spies to tenant meetings

to undermine them and gather information.

Tenants gaining the right to organize shifted the balance of power.

It explicitly protected efforts to meet and form groups for collectively

dealing with owners and landlords. Professional organizers and tenant

advocates were also protected if they came onsite to talk to people and

distribute flyers.

“I heard stories of people getting harassed, and they would take the

regulations to the property manager, who would back off,” Kane said.

It was a success story for tenants in most cases, though Kane called it “insufficient” because of a lack of enforcement by HUD.

After reviewing Peskin’s legislation, Kane said it would be “very

exciting to have a right to organize in private housing generally,

beyond HUD subsidized housing.”

He said that, if the law were passed, tenants of landlords with

multiple properties might gain bargaining leverage by uniting across

buildings.

“That could be very powerful. And everybody will see that. So tenants

will have a very strong incentive to join, and nowadays with social

media it would be possible to do that,” Kane said. “It will be a

blossoming of tenant organizing across the city.”